From Benchmarks to Classrooms: What GPT-5.1 and Gemini 3 Really Mean for Math Teaching

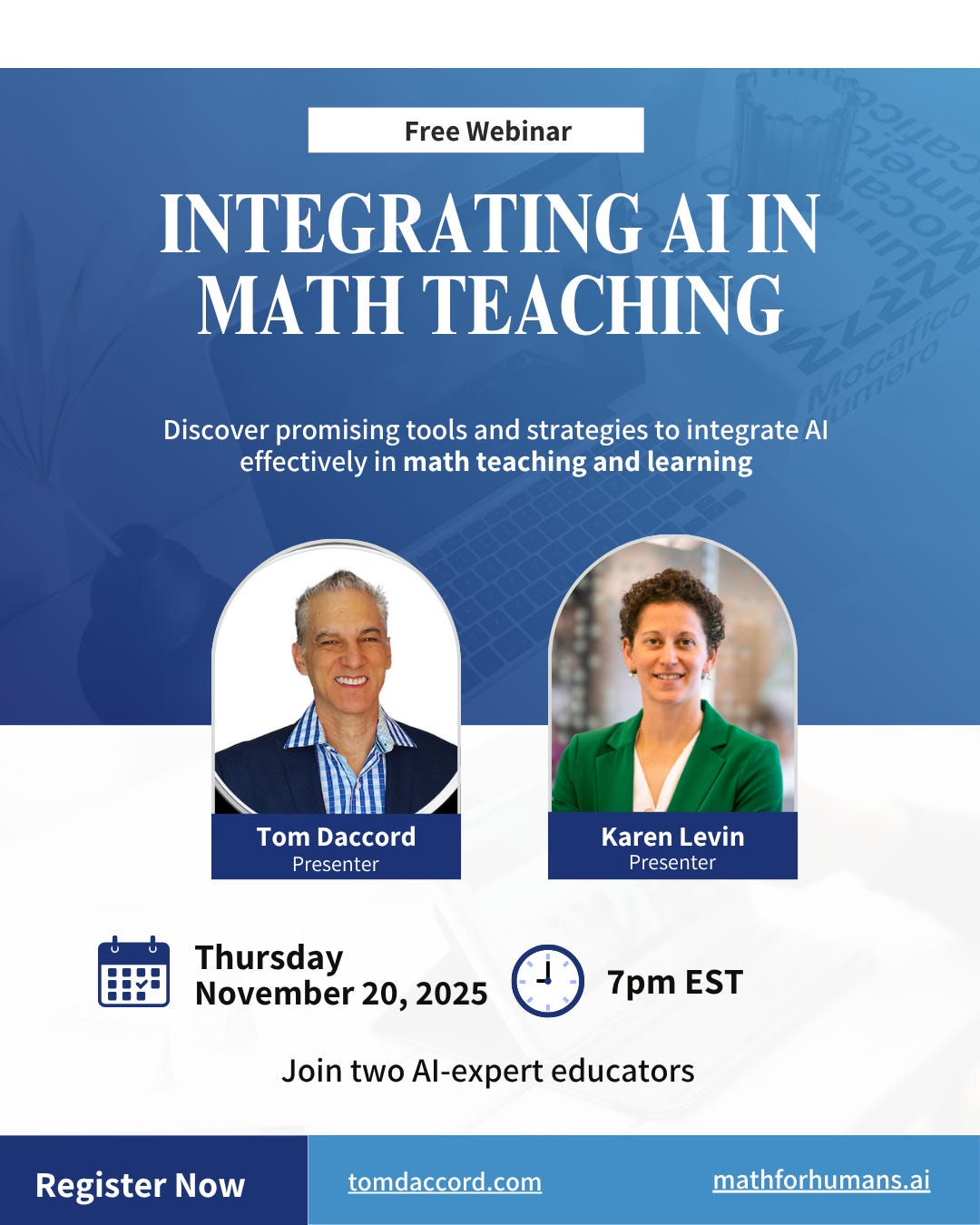

Join Karen Levin and me for tonight’s free webinar on Integrating AI in Math Teaching.

A few days ago, Ethan Mollick published a post describing how far we’ve come in the three short years since ChatGPT’s release. The gist of the article was simple but striking: Back in 2022, Mollick was amused that AI could spit out a poem about otters. Today, Mollick is now debating methodology with Gemini 3 as it cleans messy data, writes code, runs analyses, and drafts a 14-page research paper like a second-year PhD student.

Yet, despite reports on how ChatGPT and Gemini are “crushing” AI benchmarks, it can be difficult to understand how these performance gains actually apply to everyday teaching and learning.

For math educators, an obvious follow-up question is more grounded:

Does any of this actually make AI more useful in a secondary or college math classroom?

As I’ve explained, we’ve been living with an AI-in-math conundrum: the same systems that ace math benchmarks and crush math contests have also been “bizarrely bad” at basic arithmetic, geometry diagrams, or simple word problems. We read that GPT-5.1 and Gemini 3 are breaking records on AIME and MathArena, but at the same time, they still make occasional embarrassing errors on ordinary tasks.

So, what do these new benchmarks really tell us?

AIME, MathArena: What They Actually Measure

When “crushing” math benchmarks, AI systems are excelling in two prominent math-focused contest.

The American Invitational Mathematics Examination (AIME) is a selective U.S. contest that lies between the AMC and USAMO. It has:

15 relatively hard problems,

Answers as 3-digit integers,

No calculators, lots of algebra, counting, number theory, and geometry,

And a target audience of the top slice of high-school math students.

So, when reports talk about an AI’s “AIME 2024/2025 score,” they’re talking about giving those problems to a model and checking whether the 3-digit final answers match. Recent frontier models—GPT-5, GPT-5.1, Gemini 3—now do extremely well on these sets. In other words, they solve problems that stump many very strong human students.

For a math teacher, if a model can reliably solve AIME problems, then standard Algebra I/II, most Pre-Calc, and typical AP/IB Calculus exercises are firmly within its capabilities. As a measure of AI’s progress, routine factoring, solving equations, basic limits, derivatives, and integrals are no longer edge-of-capability tasks; they are non-issues.

MathArena: Boss-level reasoning tests

MathArena goes further than AIME. It aggregates recent contest problems (AIME and others) into a unified benchmark designed to be fresh and difficult for large language models. MathArena Apex is the high tier of the benchmark. It consists of elite contest problems designed to test non-routine, multi-step reasoning, creative use of multiple topics, and sometimes, careful handling of diagrams or unusual structures.

Not long ago, top models scored only a few percentage points on Apex. Now Gemini 3 Pro is being reported at around 23%—a huge leap.

What it means is that the model isn’t just running known templates. It can sometimes invent or adapt strategies for truly challenging problems. Put another way, these systems have abilities well beyond what most secondary courses demand.

But, of course, knowing something is not the same as teaching something.

Benchmarks Measure Strength, Not Teaching

Just because models can solve challenging math problems effectively, it doesn’t mean that they can teach students how to solve challenging math problems effectively.

AIME, MATH, MathArena, and similar benchmarks tell us about problem-solving strength, not teaching quality. For instance, they do not measure whether explanations are age-appropriate. The benchmarks can’t diagnose misconceptions from messy student calculations. They don’t measure whether the models can behave like a Socratic tutor and ask the right question at the right time. Nor do they measure whether visual representations, like graphs, diagrams, and tables, could deepen understanding.

In sum, GPT-5.1 and Gemini 3 are powerful enough to support a wide range of secondary and early-college math tasks. But it does not mean every explanation it gives will be mathematically sound, pedagogically sensible, or developmentally appropriate.

From Chatbot to Digital Coworker in Math Class

Ethan Mollick’s framing of the “digital coworker” offers probably the most helpful lens for understanding what has transpired since 2022. Three years ago, our AI experience consisted of pasting a problem into a prompt window and hoping the system wouldn’t hallucinate. Now, with the arrival of GPT-5.1 and Gemini 3, that process has changed markedly. These models now employ adaptive reasoning, automatically dedicating more “thinking time” and building longer deductive chains for complex problems. Gemini 3, in particular, adds powerful planning capabilities, allowing it to act less like a text generator and more like an agent that can read files, execute code, and iterate on tasks based on feedback.

In more practical terms, here are some things it can do for you now that it couldn’t before:

Take all your Pre-Calc notes and draft a concept map, create summary questions, and propose quiz items.

Analyze a photo of a student’s handwritten geometry proof that went sideways, decipher the messy handwriting to find the precise step where the logic broke (not just the arithmetic), and draft a “hint” question to nudge them back without giving away the answer.

Analyze a stack of student responses (in text form) and identify common error patterns, then suggest mini-lessons or targeted practice.

What all this means is that AI can function as a genuine teaching assistant rather than a mere computational machine. Because the models have proven their stability on benchmarks like AIME, teachers can now entrust them with bulk tasks that were previously impossible.

But They Still Make Embarrassing Mistakes

I don’t want to overhype AI’s capabilities. These models remain prone to specific, often baffling errors. A model might write highly sophisticated Python code, only to stumble on a straightforward arithmetic step. Fortuantely, these errors are rarer than before, but they are often jarring precisely because they’re delivered in an aura of certainty and conviction.

These systems can be dangerous if treated as all-knowing, but can be transformative if treated as a talented but fallible coworker.

What is emerging is the “teacher-manager” construct. We are quickly moving away from an environment where the teacher’s primary job is to catch every dropped minus sign in the AI’s output, toward one where the teacher directs the AI’s workflow. The ultimate challenge is deciding where in the learning process AI should appear, what it is allowed to do, and how students interact with it.

The Visual Aspect: Gemini 3’s Vision

A final piece of this AI-in-math puzzle is the arrival of improved multimodal vision. Earlier AI generations were essentially text-only tutors that demanded clean LaTeX or neatly typed inputs to function. In contrast, real math education consists of handwritten solutions, fuzzy photos of whiteboards, textbook diagrams, and screenshots from graphing tools like Desmos or GeoGebra.

Gemini 3 helps bridge this gap by “seeing” these artifacts much the way a human TA would. Teachers can now feed in images of actual student work for a first-pass analysis of visual misconceptions. This ability transforms video lectures and handwritten notes into computable data, allowing the AI to generate summaries or practice questions directly from the source material. While enhanced visual abilities do not inherently make these models a good teacher, they finally allow the tools to operate within the messy, multimodal environment where real learning actually happens.

How Teachers Should Read These Signals

For math teachers and department leaders, AIME and MathArena scores confirm AI “engines” are now powerful enough to handle the vast majority of secondary and early-college content without the constant fragility of previous years. However, these benchmarks measure problem-solving horsepower, not pedagogical insight.

Ultimately, we’re entering an era of the human-in-the-loop instructional designer. The AI is now robust enough to build and maintain meaningful parts of the learning environment, but it requires a human architect to ensure those tools serve the students.

Your role is to decide where the AI helps scaffold thinking and where it should be on the sidelines to preserve the struggle of learning. The benchmarks tell us we have an extraordinary engine at our disposal. Our challenge is to build a classroom vehicle that uses that power to drive understanding rather than simply outsourcing the work.

My new, free 90-page guidebook is now available for download at tomdaccord.com .

Do you have any suggestions to improve this newsletter? Please message me or leave a comment below!